This section of the website is intended for medical professionals only. To access the client page and online store, please click below.

Deciphering the chromosome 25 years ago opened the door to treat hereditary diseases

A quarter of a century ago, a team of 100 scientists succeeded in describing the chromosome for the first time. It has helped treat dozens of diseases, but its true potential is still unfolding.

It's like the invention of the wheel. It's like breaking the atom. It's like landing a man on the moon. Twenty-five years ago, that's how the media assessed a scientific discovery made in late 1999. It allowed humanity to enter the twenty-first century with the knowledge of a single human chromosome. It may not seem like much, but this research opened the way for the detection and treatment of hereditary diseases.

Simply put: most of the cases of children for whose treatment money is raised today have gained hope thanks to the description of a chromosome that has made possible genetic treatments for diseases that science had not known how to deal with until then.

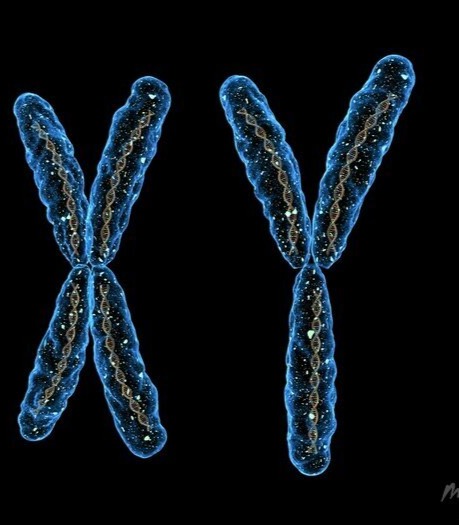

More than 150 of the top experts in the field worked on the research at the time, and the results were described on 2 December in the peer-reviewed journal Nature. Instrumentation a quarter of a century ago was incomparable to today, so the analysis was extremely challenging. The scientists deciphered a sequence in the chemical structure of the deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) of chromosome 22, one of the 23 pairs of human chromosomes. It marked the first evidence that a person's hereditary information can indeed be read literally letter by letter.

Scientists chose chromosome 22 at the time because they thought it was the shortest of all and would be the best to study. They couldn't have known they were wrong. Further investigation proved them wrong, and they chose the wrong chromosome: chromosome 21 is even shorter than chromosome 22.

The first step was the most difficult, all the other chromosomes were much easier to decipher. All of them were read in 2006, when they ended up with number 1, the longest of all. This was less than a century after the American geneticist Thomas Morgan described what the function of chromosomes actually is.

Each chromosome is made up of one long DNA molecule, coiled many times and encased in a protein component. It is estimated that there may be more than a thousand genes. Genes are short stretches of DNA carrying specific information for the construction of a particular trait or characteristic. If this molecule were to unravel, it would measure about five centimetres across.